I see people discussing the negative qualities of remakes in reviews a lot: why do remakes suck? It is a complicated discussion with many aspects.

Remakes, sequels, spinoffs and anything else that continues a previously established intellectual property are productions that start a creator on the thinnest of ice. However, it is possible to walk that frozen lake safely, as long as you take the smartest path, take your time, and give a great deal of care.

Therein lies the problem with contemporary, cynical, big studio Hollywood productions–approaching a production with eyes on the finances, and not on the quality of the product leads to bad, lazy productions that, even if they take a great deal of money and time, frequently do little more than upset the fan base it aims to extract money from.

The war on hobbyist derivation

Derivative works have been around as long as media, itself. Production is a continuous remix of that which precedes it. This isn’t bad, offensive or even questionable. It is simply a single tool that goes into the production of anything in society. We always stand on the shoulders of the giants who have begotten us. Even if we wished to create something wholly original, it would be exceptionally difficult to eschew inspiration from without–arguably impossible.

Artistic production is inherently a social and collaborative experience, passing down assets, concepts and messages from one generation to the next. For centuries, millennia, this has been part of production. Until the foundation of copyright, the very concept of deriving things was, at least on the macro scale, just the way it was.

Copyright, in and of itself, is not inherently an evil thing, either. The concept is a functionally productive one–permitting creators a grace period by which they can make a living off their creations. It is only in the most recent century and some change that copyright was perverted into a whip by which an elite few can beat the rest of us.

We have been wrestled into a situation, or perhaps duped, of shifting, globally, toward a Read/Only culture, as Lawrence Lessig would describe it–a Read/Only culture being a culture by which the populace consumes what the small class of producers create, and do not put back into the culture, themselves.

This comes through litigious and legislative control that the few large companies, led, to nobody’s surprise, by Disney. The Mouse has had such a long history of legal action and legal meddling to maintain control of intellectual property, arguably indefinitely, with no derivation permitted, even by small daycares.

Not all in the legal world are on Disney’s side. Lawrence Lessig‘s wonderful book, Remix: Marking Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy, goes into thorough detail on copyright legislation, ethics, and history. He was the author who really drew my interest onto the topic of copyright, and my thoughts on how much it needs reform. Working within art circles thoroughly dependent on the idea of remix, derivation and collaboration, I have strong opinions on the topic.

But what does this have to do with anything involving remakes and Hollywood productions? Firstly, by extending these legal snares further and further into the future, it prevents anyone else from creating a work by which they can extend their interpretation of a story onto new generations without the oh-so-generous permission of wealthy suits with no concept of who you are, nor any care of whether the work has affected you in some personal way, or not. Now, while ostensibly original works can still be derived from concepts of previous intellectual properties without stealing them wholesale, sampling and extracting pieces of culture to recontextualize them can create fascinating things.

Ironically, the very company who misers so much of their, and, due to acquisitions, honestly vast swaths of others’ intellectual property, is a company heavily rooted in highly blatant derivatives of previous creators’ works. Cinderella, Snow White, Pinocchio, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Sleeping Beauty, The Jungle Book, Hercules, The Lion King (Hamlet), The Beauty and the Beast, The Three Musketeers, The Little Mermaid, The Princess and the Frog, Tangled (Rapunzel), Oz the Great and Powerful, even releases as recent as 2019‘s Aladdin are derivatives of works by other creators.

One of the most significant ones in this line, to me, is Alice in Wonderland, based on a book that, were it subject to modern copyright law, would have been under copyright for author’s life (Lewis Caroll died in 1898) plus 70 years would make the public domain date for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in the year 1968. Disney’s production was released in 1951. This is where the contradiction becomes most apparent.

Who’s cheating who?

The health of extending culture outside of a prepackaged, focus-group-tested, sterile, corporate-approved art derivation is, thus, subject to several routes of production: those who have the money to license things (i.e. not the common creator); those who can manage the obstacle course of fair use; those who obfuscate their derivative effectively enough to declare something original; and the cavalier risk takers who will shun copyright law, roll the dice, and make derivatives despite the consequences.

Musique concrète and plunderphonic production (as a relevant example) comes into being well after these copyright laws began to spiral out of control. Sampling, likewise, is no recent phenomenon. People who consume media, who have a creative spark, may have ideas of improvements or retellings of such media.

Various intellectual property owners handle derivation in different ways, with fans responding to those different ways with different reactions, as well. I will be subjective in this analysis, as art is, inherently subjective.

Chaotic Good: A Blue Blur

Sometimes that media becomes whole new projects. One such project is that of Freedom Planet–a game with very evident roots in the Sonic the Hedgehog fandom, which, after some level of production had been completed, the creators decided to formalize the production outside of the copyright gray areas that plenty of fans hide within. Sabrina DiDuro made the decision to redirect into a course that let her retain greater ownership over the final product. However, even in her own history she cites it began as an homage to Sonic.

This game went on to succeed on its own, with a score of 83 on Metacritic. However, there is a long and storied history of delving into Sonic’s intellectual property toybox and producing media, as well as uncovering prototypes and releasing those prototypes online. Emulation, in and of itself, is a whole different can of worms to discuss, but one worm does escape this can for the sake of this discussion.

In 2013, Christian “Taxman” Whitehead and Simon “Stealth” Thomley created a mobile (Google/Apple) remake of Sonic the Hedgehog 2 with the addition of one of the Beta-aware community’s fan favorite levels: The Hidden Palace Zone implemented as a fully playable level. The fact that this is a mobile game brings up what makes this so remarkable: this fan remake was produced with support from SEGA. Whitehead and Thomley didn’t get their starts from developing games for independent studios and eventually get hired by SEGA via a resume and portfolio of original products.

These were fans who had created things derived from Sonic media because they adored it so much as children. Later, these two, under license from SEGA created an original, retro-throwback style Sonic game called Sonic Mania, a game so successful, it arguably overshadowed the Sonic Team produced Sonic Forces released the same year.

Likewise, the Tyson Hesse, artist who redesigned movie Sonic–saving the Sonic the Hedgehog movie from an unnervingly uncanny design of their mascot, likely ruining its marketability–was once a creator of a bonkers fan comic. Therein, too, is fan reception being appreciated. The backlash of the bizarre design led to a step back, reworking, and redesigning the film, something basically unprecedented in major studio film history.

These productions have all received respect both in and out of the traditional fan community. Sonic the Hedgehog went on to set the box office record for a video game film adaptation opening weekend.

So, what does this say? Well, all of these creations were adaptations produced, at least in part, by fans of the series. Jeff Fowler even directly cites fans as cultivating the success of the Sonic movie. The creation had heart, passion, care put into it. It was shaped by the community that celebrates the creation. It is a welcoming example of how embracing the fanbase can win new hearts who see what you’re doing, and how much you care about those who care about what you do.

Lawful Evil: Genesis Does… What Nintendon’t.

Nintendo…. Now I must frame this in the context of myself as a person who grew up playing video games before I begin showing just how hurt I have been by these developments.

Until 2002, I can confidently say the only Sonic game I recall playing was a Game Gear Sonic game (I don’t even remember which) that my orthodontist had in the lobby. Conversely, I grew up on Mario. I grew up heavily tied to Nintendo. I don’t honestly remember if I had a non-Nintendo system in my house before I was 10 years old.

I had a Game Boy, Super Nintendo, and Nintendo 64 all before the Playstation ever reached my house, and it was noticeably later–only after playing Spyro at a friend’s house did I even have any interest in other companies. I was a Nintendo loyalist as a young child, and even when owning systems of others, later, I still swore by Nintendo.

My Nintendo consoles had immeasurable hours on them. The only close rival might be my Playstation 2, but I assure you between Kirby Air Ride, Animal Crossing, Paper Mario: The Thousand Year Door, Sonic Adventure 2: Battle (bring back Chao Garden, SEGA,) my friend’s copies of Time Splitters 2 and Future Perfect, and the last overwhelmingly good Super Smash Brothers game (to each their own), my Gamecube discs had miles on them.

I owned a Wii, I didn’t have an XBox 360 until Banjo-Kazooie: Nuts and Bolts (which I liked, so there) came out, and only received a PS3 in 2020 as a gift from a good friend. Likewise on the Wii, I put in hours and hours between Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess, Super Paper Mario, Kirby’s Epic Yarn, Rayman: Raving Rabbids, Spyro: Eternal Night, even Link’s Crossbow Training and Wii Sports, or, further, the Mii creator, I had many, many hours on the Wii. I was still deeply enamored with Nintendo. I even put plenty of hours on Tomodachi Life on the 3DS.

Then. Once the Wii U came out, I forewent my first Nintendo console purchase of my life. I hadn’t seen any games that interested me, and went without. To this day I do not own a Switch, and that is more for what I suppose could be classified as political reasons–not governmental, necessarily, but rather the sour taste in my mouth their lawyers left after a spree of questionable-at-best decisions. Note, everything that follows, Nintendo was in the legal right to choose. However, in spirit, it goes down to the Jurassic Park principle: you can, but should you take this action?

For all the credit and adoration that the products of Nintendo have received, many fans have considered Nintendo to have fallen from grace, especially following Satoru Iawata‘s passing. KnowledgeHub does a particularly decent analysis of Nintendo’s sins, since then. Public relations would not be defined as Nintendo’s forte.

This is not the sole video on this topic, though. This is analyzing its focus on business over creation, and issues that dissatisfy and push away developers. The more important issues, which in some ways do coincide with Iwata‘s time in charge, are the anticonsumer choices. Some are willful apathy to their paying consumers, others are litigious actions such as: copyright claiming game soundtracks, despite not placing them online, officially; limiting purchase time of a game release (more than once), while also poorly emulating their own games–when cracking down, hard, on emulation; notorious artificial scarcity issues; nixing games off the e-shop and rebooting the e-shop from zero when a new system comes into existence.

And the huge controversies. Firstly, in 2020, when we were all holed up in our houses due to the -Itis, The Big House wanted to run a Super Smash Bros. tournament series which had a Melee tournament within the event–for this to work, the games had to be emulated, using Slippi, a mod that made the game online-compatible. About a month before the event, Nintendo pulled the plug due to the required emulation–even if the people owned the disc and extracted the file, themselves. They also canceled the newest Smash tournament, despite not requiring emulation.

They further hurt their own PR by shutting down a Splatoon 2 tournament the day before the event, because some of the creators named themselves #FreeMelee in solidarity with the Big House Super Smash Bros. tournament cancellation.

Further, they have a history of sending out copyright notices for fans creating unofficial, unpaid derivative works of their intellectual property. They attempted to end game rentals, failed miserably at attempts put restrictions on monetizing let’s plays–but only after 5 years of struggling, attempted to end Another Metroid 2 Remake, and Pokémon: Uranium Edition, as well as a level designer called Super Mario Bros. X.

Before I address Super Mario Bros. X, I need to put some context on how much love there is for Mario level design and editing, drastically predating Nintendo ever providing access, themselves, to the opportunity. This, also, includes massively more powerful, flexible, and intuitive tools five, ten, and even fifteen years prior.

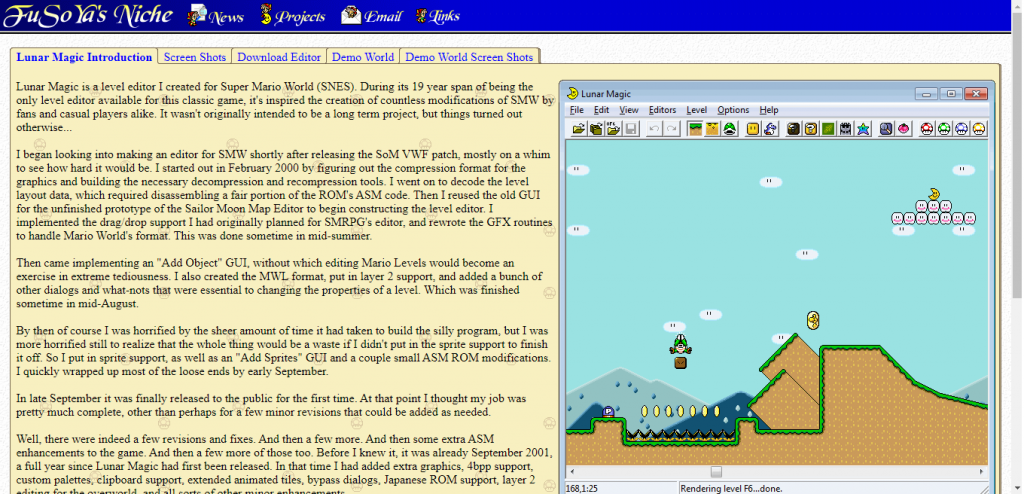

There is an enormous amount of history with the previously hinted can of worms and emulation. As I have said, whether it has value or not is a conversation worth its own article (though for the record, I support emulation.) However, I can address, here, my time spent watching Let’s Plays, which often involved hacks of Super Mario World using (various tools, honestly, but chiefly) Lunar Magic.

Lunar Magic is a phenomenally powerful tool, which allows people with a ROM of Super Mario World to create their own levels, implement (produced outside the GUI) custom graphics , custom sprites, custom music, custom scripts, custom everything. The community surrounding Lunar Magic and the whole of Mario hacking is vast, and toes very thin lines. I adore Lunar Magic and how flexible, yet intuitive it is.

There was, however, one other tool: Super Mario Bros. X. Andrew “Redigit” Spinks, the creator of Terraria, once was a producer of another impressive Mario custom level tool, before Nintendo’s lawyers came ringing on his phone. The claim has some level of dubiosity, but isn’t outside the scope of Nintendo’s pettiness, as I will demonstrate. Further, many accept it as truth, considering how much content was lost in the-at the time-closure of the project. However, to this day, fans have taken the mantle, and continue to update the project, despite Spinks‘ departure from the project.

I would posit that both of these far outclassed the qualities of Nintendo’s own level makers. Both are more robust and flexible, and both predate Super Mario Maker, in the case of Lunar Magic, by roughly 15 years.

Further, while Nintendo has put stoppers on fan projects, they also won’t make things that fans demand, meaning those fans have no outlet, self-made or Nintendo-made, to continue enjoying series they love. It was a problem with Metroid until recently. It is a problem with Star Fox. It’s an issue with Mother, whose third game, despite fan acclaim, has never had an official English translation. Any side characters fans love will likely never get focal games. Plenty of old titles which never made it to the virtual console (or were on retired systems’ virtual consoles, whose shops are no longer supported will be inaccessible, per Nintendo’s opinion on regulations.

Generally, Nintendo has an antiderivitave stance, which upsets fans, PR-wise, and limits the opportunities for developers to learn how they have, for decades, to design games and levels.

True Neutral: ZZT and Abandonware

ZZT is a DOS game created by Tim Sweeny (CEO of that Epic Games) in 1991. It has an in-game level editor, and, to this day–despite the last sequel of the game being released in 1992–thirty years later, there is still a huge fan community creating new levels, modifications, and artwork from within the game engine. It has remarkable fan longevity for a niche game you may have never heard of.

Fans have expanded the life of a(n, especially by modern times) small–MS-DOS–game from three decades ago simply through their passion–and the game, itself’s flexibility.

Mod support and game flexibility is, indeed, a fantastic tool one can use to make a game’s memory last a long time. Even a map editor can extend the life of a game by a great deal–going beyond that is only going to further the life that game lives.

And, further, to the crux of my point that all this points to, even if it feels rather round-about. As Sonic, as ZZT, as games such as Cities: Skylines or Minecraft demonstrate. Fans create content that other fans enjoy, which keeps your product relevant, and promotes healthy interest in your product. The fans are what make a creation succeed.

Irking the fans can do a great deal of harm. Derivatives do good for a product. Devolver Digital has a loving embrace of let’s plays, because they see how much it builds interest in their products. I have purchased plenty of Devolver games due to their stance, and my appreciation for it. I have bought many games I have watched others stream or let’s play due to seeing how good the game is. I’ve gone back to Minecraft on probably 4 or 5 occasions after long gaps of time, simply because I saw others playing it.

So, fans can make good products of derivatives. Fans can make products succeed by putting passion, soul, and originality into media that they adore.

So let’s take a look at the other side of the coin: Hollywood.

While the Sonic movie, being made by Paramount is, indeed a Hollywood production, I argue it is a phenomenal exception to the rule, and not the rule itself. While any film will have its supporters and opposition, I want to focus on the consumer, here. I want to focus the eyes on how the people actually making up the populace who supports the media.

DO Remakes Suck?

Let’s take a look at some remakes, reboots, soft reboots and spin offs that have come out in the past few years:

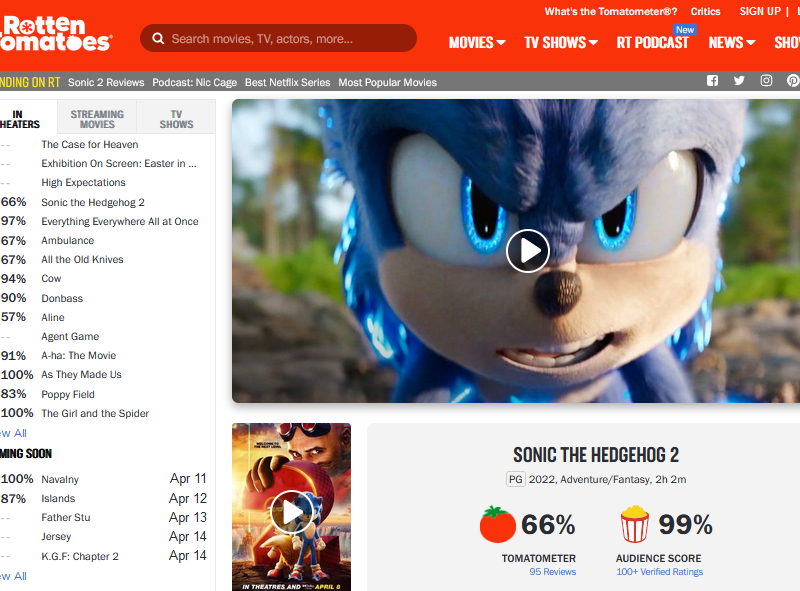

Mulan has a user score on Metacritic (as of January 20, 2022) of 2.9. Cowboy Bebop got a 5.2. Aladdin manages to eke out a 6.7! Matrix: Resurrections has a user score 3.9. Halloween Kills has a 5.6. Independence Day: Resurgence received a 4.5. Star Wars: The Last Jedi earned a middling-at-best 4.1 (for comparison, the notorious Phantom Menace has a 6.1.) Men In Black: International has a 4.3. Resident Evil: Welcome to Racoon City got a 3.5.

Now, there are important things to note: not every remake fails. Artistic qualities are subjective. Scores can be negatively (or positively, note) manipulated to some extent with campaigns. Plenty of independent products and even fan creations can be absolutely awful. However, to each of those points…

Plenty of diamonds will come from the rough, and without knowing the personal life of the creator, it is hard to say whether the creators are in it for the money or love of the craft. I would speculate, however, that the more successful reboots and adaptations have creators who have a passion for the product. Other times the passion leads to accurate creations, but audiences aren’t prepared for such things. Everything is complicated.

This is nice and all, but why do remakes suck?

Artistic qualities are subjective, but generally a large enough group of people (not every Metacritic or Rotten Tomatoes score has a significant sample size, but they’re the largest sources you’re going to find) are going to suss what the zeitgeist says about a product. But it is completely within the playing field that art is nuanced and complicated, and each person has their own perspectives that can make the “worst” creation have sincere fans and the “best” creation have detractors, I agree.

While there have been claims of review bombs, and I can imagine an angry dude and ten of his friends trying to create some sort of group that does such things, but I seriously speculate that it is finger pointing and, at best, the stand alone complex in the majority of these cases. I have no evidence, as that would be very hard to provide, but it is simply the stance I take from things.

Mob rule certainly can happen in the online sphere, but I just don’t think people always have the drive to do something like this, as it has little to no benefit to them, overall. It is possible, but, I feel, unlikely. Especially because most people go into a movie, or buy a game, or read a book to be entertained. What good is it to spend your hard earned money to be, willingly, disappointed?

As far as fan creations versus big studio creations, this is an uneven playing field. Most people are not versed in production of things well enough, especially when they first get that creative spark, to create professional quality products. The percentages are going to skew, as Sturgeon’s Law dictates, more heavily, with untrained creators, even if they have the passion. However, Hollywood is (hopefully, though I often question) not a bunch of untrained creators.

Hollywood is, ostensibly, the best of the best, hired by corporations whose goal is to access the people most qualified to produce the thing in question. While, yes, junk will sometimes surface, you would hope that the talented, trained, educated creator with a portfolio and studio backing with large sums of money would at the very least be competent.

![Intro / Opening - MLP: FiM [Español Latino] - YouTube](https://external-content.duckduckgo.com/iu/?u=https%3A%2F%2Fi.ytimg.com%2Fvi%2FJXPpK9gu-XQ%2Fmaxresdefault.jpg&f=1&nofb=1)

Herein lies the issue. It isn’t the competency that is the issue with corporate producers. It is the passion. Untrained fans can make trash, or spin gold. However, the fact that a passionate, but untrained individual can create a great product, but an apathetic individual seems destined to create a–perhaps pretty but ultimately–mediocre at best product. If you have no passion, no heart, if it’s for the paycheck and naught else, there is no drive to do more than, arguably, the bare minimum.

This is, ultimately, why there are so many disappointing remakes. You, as a viewer, have intention of going into a production to match your personal experiences with a source–such as Sonic. You know what it is you like about it, and what that history is. You know, at the very least, a surface level of knowledge beyond what a few commercials and ten minutes of someone else on YouTube playing a game is going to give you. You have expectations, opinions, care, and passion.

A creator making something for the paycheck doesn’t share those interests. They know what their instructions are, and how to tell people what to do (usually based on some general populace focus groups and a couple synopses of the concept, at least.) They don’t have a personal touch related to the topic, necessarily, so if things seem off, or don’t mesh with logic. Though, even fans can be pushed by executives to make strange choices.

The biggest thing in someone’s eyes in a corporate machine is going to be making money. The people in suits often don’t care about if it is loyal to the source. They don’t care about the fans, themselves. They care about public appeal and getting the fans as some free bonus income along the way. That is why remakes tend to the mediocre at best. However, there is also a slight bit of responsibility on the fans, too.

Fans do have expectations, and sometimes those expectations may be unfeasible. I have seen plenty of adaptations and remakes where what I wanted didn’t come to be, and, in reality, I don’t know what I expected. It’s not like a shot for shot remake does anything except increase the resolution of a film–and that’s in the best of circumstances. Things are going to change. Things aren’t going to match your ideal. You have to have a bit of give and a bit of take.

All in all, remakes and reboots will always be contentious. However, I feel, at the end of the day, for them to have any real longevity and respect, the creators of the project need to have some personal attachment. If it is a cynical cash grab, people will see it from a mile away–it’s just about being smart enough not to take the bait. Don’t reward studios for exploiting you. —Tails_155

For more from me, check out Visual Signals: Issue Six!

One thought on “Why Do Remakes Suck? The Hidden Story of Reboots, Fan Productions, Passion and Cynicism”

Comments are closed.